CHAPTER 3

REBIRTH!

“Rogers,” General Anderson said quietly, as the car began its trip back to Manhattan, “if you could change anything about yourself, what would it be?”

“Be, sir? You mean like smarter, bigger, tougher, like that?”

“Like that, yes.”

“Well, I suppose every man who’s something less than physically perfect wishes he had a new body.”

“Yes, exactly. And would you like a new body?”

Rogers turned to stare openly at the general. “Sir? I don’t get the joke.”

Anderson smiled. “No joke. Seriously, we are in a position to offer you, well, not a new body, but—a better one.

“As you know, you were selected to be among our guinea pigs for a new experimental project. That project is officially known as Operation Rebirth.

“If the experiment is successful, you will grow and develop a new, stronger, tougher, bigger body. And not only that: Your body will be able to withstand extraordinary punishment. Wounds should heal in half the usual time, or less. You should be almost entirely disease resistant. You’ll be able to function over a wider heat range—from numbing cold to blistering heat. Your metabolism will be capable of being speeded up at will. Sound good?”

Rogers nodded. “And—if the experiment is not successful?”

“I won’t mince words with you, son. It could kill you.”

The Hudson’s headlights picked out the sights of shabbily dressed men leaning against storefronts, others sitting or sprawling in doorways. Always nearby was the twisted brown paper bag, a bottle poking slyly out. Overhead, the Second Avenue El trains rumbled by, their vibration visibly shaking the rows of support pillars rising from the curbs.

This was the Lower East Side, a dismal slum that would not have changed appreciably long after the El tracks had been removed, and modern street lights installed.

Here the homeless bums, winos, the human derelicts lurked and lived. Here too, rats the size of cats fearlessly invaded shabby apartments to steal a starving family’s last remnants of food.

It was an anonymous place, the sort of area in which anything might go, because its denizens were an incurious lot, who accepted within their midst every kind of underworld scum. If one wanted privacy, there was no better place than among the teeming populace of the Lower East Side.

Brown swung the Hudson off onto a side street, and up to the curb. This street was a typical mixture. Side by side sat tenements, a rundown apartment building, a deserted warehouse with crude obscenities chalked on its doors; and, next to that, a dusty curio shop—the kind where one can buy or sell anything, few questions asked.

Brown remained in the car, while McInerney, letting Rogers and General Anderson out, led them directly across the sidewalk to the entrance of the curio shop. A bum, filthy, unshaven, reeking of alcohol, was sprawled across the doorway.

“Out the way, you,” McInerney snarled loudly. Then, in a whisper Rogers barely caught, he added, “Everything okay?”

The burn opened a surprisingly clear blue eye, winked and nodded, and then grumbled, “Okay, mister, okay.” He sidled off the step.

McInerney pushed into the shop, stepping aside to let the other two past, and then closed and locked the door. A bell over its sill jingled.

“Coming, gentlemen, coming,” called a querulous voice, and from the dim interior shadows of the shop stepped a huddled old woman.

“I believe you were expecting us,” the general said.

“I expect nobody,” she replied. Her hand brushed against her long full skirts, and then held an ugly short-muzzled automatic. “Your identification, please. Place it on the counter, then step back.”

Each of the three men in turn surrendered his papers, Rogers passing over his expressly issued photo-card.

The woman switched on a bright light which caught them in their faces. Rogers blinked and then closed his eyes. The light was blinding. Then it was off, and it was like a pressure being removed.

“Thank you, gentlemen. Shall we proceed?” She turned and started toward the back of the shop. McInerney scooped up the sets of identification papers and passed one to the general. “I’ll keep yours,” he told Rogers. “It wouldn’t do you any good when you come out, anyway.” With firm strides, the woman led them to a back stair, and up to a second-floor hall. Boxes, most of them open and full of old appliances, tea services, and other household oddments of other eras, lined and littered the length of the hall. Midway down, the woman motioned them to a stop, and squeezed between two stacks of boxes. Next, a crack of light appeared on the wall. The crack widened, and became a narrow open door.

Rogers tried to remember the layout of the building as he’d seen it from the outside. This hallway should be running down one side of the narrow shop. And the doorway was on the outside. That meant—she was leading them into the apparently abandoned warehouse next door.

Steve Rogers was to know that warehouse intimately, for he spent four weeks there, sometimes confined to his bed on the third floor, sometimes prowling the fourth-floor lab with Dr. Erskine, sometimes chatting with the security men on the second floor. It was only the first floor he never saw. And that, he had been told, was sealed off from the upper floors, a dusty, musty area that looked exactly like what it was—part of an abandoned warehouse.

The upper floors of the warehouse constituted one of the most advanced laboratories in the United States. Under the direction of Dr. Anton Erskine, pioneer research was being done into the biochemical areas of human physiology. Although Dr. Erskine delegated much of the work to his assistants, he alone held the key knowledge that crystallized their findings. “It is very simple,” he had once told General Anderson. “I can commit everything to paper, and sooner or later the wrong man will read it and steal it. Or I can keep it all locked in my memory, where I know it is safe. Eh?”

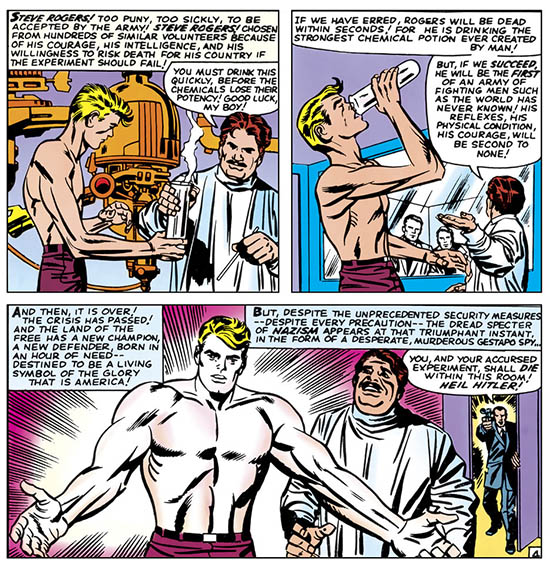

Steve Rogers had been analyzed. His entire body chemistry had been analyzed. The very genetic structure of his chromosomes had been broken down and catalogued. Dr. Erskine had already unlocked the secret of DNA and RNA—a secret which science would not penetrate again for two decades.

Now Steve Rogers’ body structure would be changed. It meant days of careful preparation. Everything followed the necessary sequence.

First his bones were strengthened. This was done in two different ways. The first was a series of operations on his arms and legs, in which stainless steel-slotted tubes were inserted within the marrow of his bones, adding enormous rigidity. Next, while his diet was heavily weighted with calcium, a series of chemical treatments built up the very structure of his bones, strengthening them, making them less brittle, more resistant to impact, and capable of carrying greater weight. During this period, Steve felt awkward and ungainly, like a wobbly colt just learning to walk. He had gained three inches in height, and his shoulders and chest had swelled. Yet he was underweight, skinny, and his new bones made it only more obvious.

Next came the muscle build-up.

Each day they injected him with chemicals, fed him enormous meals, rich in proteins—eggs, cheese, steak—and put him through wearying calisthenics. One part of the third floor had been fitted up as a gym, and each morning a burly man with little hair and a mashed ear would lead him through a series of torments designed to exhaust him completely. First, twenty laps around the gym and a workout on the chinning bars. Then the rowing machine. Then a nap and a meal. Then another twenty laps and pushups. And so on, into, it seemed, eternity.

He lost track of time and of the days. There were no windows in this building, and the hours passed in blurs.

But one day he walked past a mirror, and saw a stranger staring back at him. He paused, and looked wide-eyed at the sweaty Greek god in the glass. He looked at his heavy shoulders, the broad chest, thick biceps and triceps, the piston-like forearms, the supple, tapering waist, powerful thighs, and muscled calves. It was like looking at a total stranger. And yet it was he—Steve Rogers. He shook his head in amazement.

“You’re doing fine, son,” Dr. Erskine told him the next morning. “You’re living proof that my program can be successful. Can you see Hitler’s face, when we throw an entire army of guys like you at him?”

Rogers smiled, modestly. “It doesn’t seem real, sir. I guess I just haven’t had time to accept it. I’ve been so tired, so exhausted lately.”

“Of course. We’re speeding up the development of your body. It takes more food—energy—more rest and sleep. All that meat on you didn’t come from nowhere!”

“I’ve been worrying about that, sir. Are you sure it’ll stay? I mean, if I ever go back to a more normal life?”

“Don’t worry. What it all boils down to is your genetic pattern. Every cell in your body had imprinted in it the whole pattern of what you are, what you should look like. Theoretically, given one cell from your body, we could reconstruct you. This genetic pattern is what controls what you are—whether you have blue eyes or brown, how tall, how heavy you’ll be—everything.

“What we’ve done is to change your genetic pattern progressively. We’ve told your body that it shouldn’t look like it did—but rather the way it does now. Give it a normal amount of food and rest, and it will keep the new pattern. Don’t worry.”

“Is that all there is to it, sir?”

“No, we have a few more things to take care of. We want to give you a wider operating range. We want to give you faster reflexes—an altogether faster metabolism, in fact. And we want to increase your tolerances to heat and cold beyond the human norm. This will be the most dangerous part of our program because, you see, we’ll be tampering with aspects outside human normality. Up to now we’ve just shuffled your genes around within normal human limits. Now we’ll be attempting something nature has never tried.”

Rogers felt a chill come over him, a chill that had nothing to do with the perspiration still wet on his body from the early morning workout.

“You mean, sir, that I still stand a chance to lose all this? To come this far, and…?”

“Want to stop now?”

Rogers felt his face heat. “No sir. I volunteered for the whole program, and I’ll stick to it.”

“Good.”

The next twenty-four hours were the strangest Rogers had ever known. He was strapped into his bed, and given an injection.

It seemed only a pinprick-moment after the needle had been withdrawn from his arm that his sensations began to turn rubbery. His eyes were still open, but the room seemed to shift and recede into a vague combination of colors that clashed, and disturbed him. So he let his lids close, and a warm, rich blackness swept over him, all but drowning him, until he replaced it with new visions.

From some faraway place, he heard the drone of voices, sounding muffled and doleful, like a recording suddenly slowed to half its speed; deep drawling voices. They spoke words, but not in any way intelligible to him.

The voices disturbed him, so he willed them to stop, and spun them away from him. He watched them recede like distant comets into the black infinity of space. Then he somersaulted himself one hundred and eighty degrees, and set off in the opposite direction.

He was hallucinating, he knew that. In one astonishingly lucid portion of his brain he was totally aware of everything going on, of the voices in the room, and what they were saying (it would be filed away in his memory to be taken out and examined later), of his own strange reaction, and of the vast vista of wonderment opening up before him.

He felt like a child, bright-eyed and eager, while, coldly aloof but not unfriendly, his superego sat upon his shoulder, observing, recording, making a note of everything, interfering in nothing.

What did it all mean? It didn’t have to mean anything at all. Experience was its own justification. Being was being.

Later, when he described his experiences, or attempted to describe them, to Dr. Erskine, the man shook his head wearily and said, “Perhaps you have undergone a transcendental experience. Or perhaps you just went temporarily mad.”

“Mightn’t it all be the same thing, sir?”

“I don’t know. I’m an old man. I’ve never fully accepted Freud. Jung I can’t understand. I just dabble with chemicals. I don’t know.”

And Rogers had felt sorry for him; sorry for any man who could do so much, and still not know.

Gradually the hallucinations ceased and he found himself returning to his own body. Yet it was a different body, different from both his first, scrawny body, and from the new physical perfection of the second.

The difference was that of control.

For the first time in his life, he felt truly aware of his body’s functions and abilities. He caught the sound of his heart pumping, and then the feel of it. He followed the surges of blood throughout his entire circulatory system, and in the process became aware of his nervous system—that vast communications network of nerve ganglia. He followed the autonomous functions back into a portion of his brain he had never known before, connecting it as he went with his ductless gland system, with its manufacture, control, and release of body and brain chemicals and hormones. Here, in this newly discovered part of his brain, he found the origin of the messages which controlled his heartbeat, connected the smell of food with the salivation glands in his mouth, and performed all the other bodily functions normally beyond the awareness and control of a human being.

And with his awareness came control.

He found himself speeding then slowing, his heartbeat. He deliberately increased the amount of adrenalin in his bloodstream. He manipulated his optical nerves, and tightened his optical muscles to correct his nearsightedness. Bit by bit, he took a tour of inspection of his own body, making corrections as he went, easing out malfunctions here, tuning up a little there, until he not only knew exactly how every aspect of his body functioned, but had put it all into perfect operating order.

Then he fell asleep.

When he awoke, he felt more refreshed than he had ever felt before in his life. He was puzzled for a long moment. Then memory came flooding back over him. He lay still, his eyes closed again, until he felt he had digested it all, and understood it.

He no longer felt that total control—that tuned awareness of his body. Yet he knew that he remained in control, if only subconsciously. The injection he had been given—he didn’t know what it was—had placed him in that lucid state in which he had checked himself out so thoroughly. The drug was exhausted now, and he would be on his own. But enriched.

He felt amazed at all he had learned about himself. He had known, in a vague and meaningless sort of way, that the human body has great reserves of strength and power which it normally never uses, but the knowledge had never meant much to him; he had felt too far removed from the reality of it.

He had gone to a show once, where a hypnotist had put a volunteer into a trance, told him to become as stiff as a board, and then had demonstrated the man’s amazing reserve of strength by positioning his head on one chair, his heels on another, while directing other volunteers to sit and stand on his unsupported torso.

It meant something now. Steve Rogers knew that if the occasion ever arose, he had a great reserve of power he could call upon and will into use. He knew too that he could speed or slow his reflexes at will. There would be a price paid, of course, for each feat of strength and will. The energy needed would have to come from somewhere. He could deplete his body badly if he didn’t restore it with additional sleep and food—the sleep to rid his body of toxins, the food to refuel it.

He pulled himself upright and sprang to his feet. Now he could truly understand and appreciate the new body he had been given. Now he could exult in it!

Please Support Hero Histories

Visit Amazon and Buy...

The long out-of-print first Captain America novel!